Paradise on the James

Published 2:54 pm Monday, October 22, 2018

Story by Phyllis Speidell

Photos by John H. Sheally II

For decades, Respass Beach has seemed far removed from its neighboring Churchland, Harbour View and the high speed I-664 in North Suffolk.

Folks well past their childhood still speak nostalgically of her sandy beaches and shallow waters that were wade-able almost halfway across the James River. They remember stands of pines, cedars and hollies thick with wildlife. The river and creeks were full of fish — flounder big as a cooler lid, they say — as well as oysters and crabs that could be scooped up by the dozen. They remember the Saunders’ peach orchard just off Respass Beach Road and the flock of peacocks whose screeching carried throughout the community.

When Portsmouth artist J. Robert Burnell was a youngster battling scarlet fever, he dreamed about the cold clear well water from a pitcher pump near the beach.

Respass Beach was an oasis for Burnell and others who loved its privacy and lifestyle.

“It was a paradise,” agreed Ralph Hicks, a retired banker living in Virginia Beach.

Hicks was growing up in Cradock when his father, a foreman at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, partnered with a coworker, Morris McCarty, to buy 85 acres of land at Respass Beach. In the late 1940s, $15,000 was a hefty price, but Hicks and McCarty saw potential in the property. They divided the riverfront into 18 residential lots lining an unpaved road. They sold the first lot, a few years later, for $2,000.

They rented out rowboats with cinder block anchors and built a concession stand for beachgoers. Burnell remembers “Old Man Respass” who ran an earlier snack stand in the 1930s. Hicks remembers the beach sand as “so terrific some people tried to steal it.”

The partners later leased the boat operation to a man named Barnes who also bought property there.

Both Burnell and Hicks recollect an oyster shack, once owned by the J.H. Miles & Company Norfolk seafood dealer, on pilings in the waist-high waters of the James and the popular, albeit illegal, “jalopy track” that staged weekend races not far from the riverfront. Eventually, Nansemond County wanted to buy the racetrack to build homes for lower income families, Hicks said, adding that the decision to give up some of the area’s privacy was a real dilemma for his dad, who finally agreed to sell the land.

“My father built a cottage, the Pappy Shack, there on Streeter Creek,” Hicks said “Still near and dear to me and my kids, it was only about 15 x 15 feet, almost surrounded by water and had a little pier where you could fish and crab. We used to have oyster roasts and went rabbit and squirrel hunting. We gathered mistletoe and holly and I peddled holly wreaths door-to-door every Christmas for spending money. ”

An anti-aircraft artillery unit operated in Respass Beach during World War II. Burnell said his Boy Scout troop often camped near the battery. After the war, the government left the de-activated battery in place, and the senior Hicks opened a restaurant — Hampton Roads Terrace — in the building. The business was short-lived, however, Ralph Hicks said. One Sunday about 1950, the Nansemond County sheriff ordered a glass of wine with his meal. When he was served, the sheriff shut down the restaurant as being in violation of local liquor laws.

Elgie Furman Lilly, 91, remembers Respass Beach as “hidden for a long time and a very unique community of the haves, have-nots and don’t-cares.”

Lilly was a timekeeper in the Norfolk Naval Shipyard where she met her husband, Jack Furman. Furman came from generations of watermen, so it wasn’t surprising that his parents, John and Lillian Furman, were among the several families buying multiple lots in Repass Beach in the mid- 1950s. Shortly afterward, the younger Furmans decided to build a house next door, also on the riverfront.

“The lot was a wilderness that we cleared by hand with dynamite — it took a year,” Lilly said. “Jack went on night shift so he could work on the house in daylight. He built a solid home — three bedrooms, living room, dining room, kitchen and bath — standard for the time.”

Children were safe to roam in Repass Beach, she said, but the dirt streets were often muddy, so residents carried shovels in their cars. John Furman was still oystering and, along with friends, spread oyster shells on the road. Residents picked up their mail in Churchland and sent their children to Nansemond County schools. They shot skeet in their backyards, fished, boated and relished their privacy.

“It really was a paradise,” said Burnell, who remembers spending time there as a child and later, too, when he was married to Lilly’s sister.

Burnell’s son, Rick, also remembers Respass Beach well — John and Lillian Furman were his grandparents.

“I spent the first six years of my life with my grandparents, living in Respass Beach, and later I still spent a lot of time there,” he said. “The best fishing was after dark, so I would go out with a lantern and a basket roped to my waist. I carried a net and speared flounder and softshell crabs.”

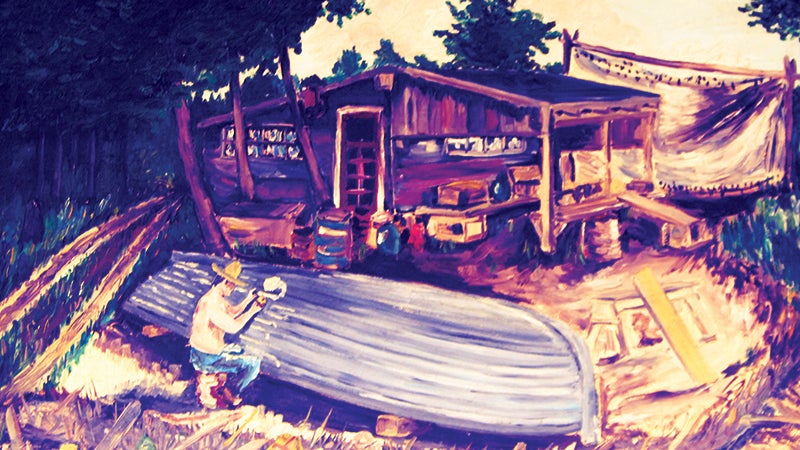

John Furman, Jack Furman’s son, keeps an early Burnell painting in his Portsmouth office. The scene of a Respass Beach waterman working on his boat in the spring triggers memories of growing up there.

“The greatest thing about living there was being able to play on and in the water,” he said. “I went out with my father oystering and fishing. I would cull. He probably made more selling seafood than working in the shipyard.”

Hurricanes were hard on the community, sometimes lifting large boats from yard to yard.

“We used to make our pier from whatever washed up after a storm,” he said “When the Ash Wednesday Storm buried my father’s boat in sand, his shipyard friends dug out the boat and fixed it all up. They didn’t want to lose their seafood supply.”

The Furman family also remembers when a 60-foot whale stranded in the shallow beachfront waters.

Jackie Taylor moved to Respass Beach in 1996 and remembers when the roads were finally paved; the grateful neighbors threw a party to thank the contractors. Now several times a day, he bikes the 8/10-mile circuit around Bay Circle, often meeting walkers and runners on the way.

The face of the Respass Beach changed again as more newcomers fell in love with the view they describe as seeing forever — eight clear miles to the northeast with nothing in the way.

Keith Horton, president of the Holly Acres, Respass Beach Civic League, and his wife, Peggy, moved into their riverfront home on July 1, 2006, after buying the lot and clearing the small home there that had once belonged to the Swindell family.

“From the back yard you can see two bridge-tunnels, Hampton, Newport News, Portsmouth, Norfolk and the shipyard in Newport News, “ he said. “We watched the USS George H.W. Bush under construction and while we watched the history of the Battle of the Monitor and the Merrimac on television, we could look out the window to where it all happened.”

“This is the friendliest neighborhood I’ve ever lived in — a mix of individuals and backgrounds,” Horton added. “Neighbors want to keep this place the way it is — one way in and one way out.”

The Respass Mystery

J. Robert Burnell was 8 years old when he met “Old Man” Respass. Now 80 years later, he, like everyone else we asked, cannot remember the first name of the man for whom the area is named.

Gwynn Henderson, a historian and genealogist from Gwynn’s Island and a Respess family descendent, has tracked her family history for years. The search has been complicated by the loss of Mathews County records during the Civil War and the inconsistent spellings of the Respess name since the earliest record she found — a 1704 mention of a Christopher Rispus in Gloucester County.

She learned that while most of the Respess family remained in Northampton and Mathews counties, some ventured to Surry County and North Carolina. Henderson said she would not be surprised if “Old Man” Repass was somehow connected to the Surry County branch of the family.