A Polish outpost in Western Branch

Published 6:51 pm Thursday, February 15, 2018

Tucked away between the Great Dismal Swamp and the confluence of highways at Bowers Hill loathed by motorists is a quiet little community called Sunray.

In Sunray, chickens roam free, residents take care of each other and Polish culture and American determination are treasured.

The settlement is among the lone southern outposts of Polish immigrants and their descendants, who mostly preferred the Northeast and upper Midwest. The story of how they wound up here — and stayed here — is one of deceit and determination.

“That little community, if they didn’t have their faith, I don’t think it would have even been possible to survive, because it was tough times,” said Mary Ann Wagnstrom, a lifelong resident and treasurer of the Sunray Farmers Association.

According to the application for the district’s inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places, the land was platted in 1908 by the Southern Homestead Company. A year later, the Virginian Railroad was established.

The United States Colonization Corporation was formed in 1915 with the primary purpose of attracting immigrants to the area. Between 1915 and 1918, they sold numerous lots to Polish farmers who arrived to find that the land was marsh.

Undaunted, the farmers dug their own ditches by hand to drain the land and built their own homes with lumber from the Great Dismal Swamp.

“They had to work together as a team to do all that clearing,” Wagnstrom said. “It was an unbelievable amount of work.”

The settlers constructed St. Mary Catholic Church in 1915-1916 in the Gothic Revival style. The Farmers Political and Industrial Association of Bowers Hill was formed in 1921. In 1935, that name changed to the Sunray Farmers’ Association of Bowers Hill.

By 1920, there were about 40 homes in Sunray, most of them modest single-family farmhouses of one and a half or two stories and constructed of wood that the settlers harvested from the swamp themselves.

The community self-sustained with farmers’ crops, and the produce was also sold at market.

The post-World War II boom brought more houses to Sunray. A daily bus ran between Sunray and the Norfolk Naval Shipyard during World War II, which provided outside employment for many Sunray residents.

But even though the area has grown significantly, few who are not immigrants’ descendants have come in.

“We’ve still been able to retain quite a bit of farm even though it’s a pretty high-density area now,” Wagnstrom said. “They haven’t been able to break in because of the way the plots are laid out.”

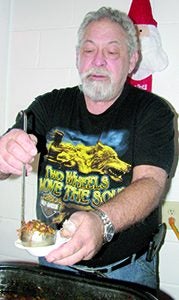

John Lezon serves up venison stew. He’s a New York native of Polish descent who says he’s “Virginian by choice.”

Families farmed together and raised their children in a communal environment. Everybody knew everybody.

“When you talk about it takes a village to raise a family, that’s what it’s all about,” Wagnstrom said.

These days, the village remains a close-knit community that retains many Polish traditions.

“It’s a nice community,” said Charlotte Rohlf, whose family, the Biernots, was among the original settlers and has a street in the community named after them. “I still love living in it. When I was a kid, we never locked our doors or anything. We left our toys out and nothing would ever happen to them. We all were very close.”

Polish culture is evident at events like the annual Taste of Sunray in December, a fundraising event for the Farmers’ Association. Dishes like kapusta, a stew made with sauerkraut or cabbage, ketchup and other ingredients, as well as pierogis and sausage, are common.

Visit the Facebook page of Sunray, Virginia Historical Polish Settlement to see details on upcoming events in Sunray.