Mapping the Old Dominion

Published 5:05 pm Thursday, January 24, 2013

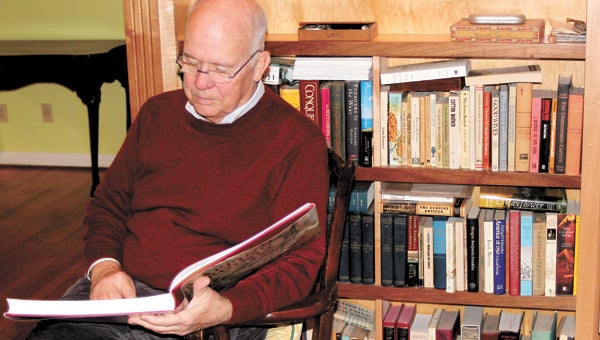

William C. Wooldridge of Bennett's Creek reclines in his home library with a book he has compiled on the largest private collection of Virginia maps, which he assembled during the course of about 40 years.

John Bachmann supported his family as a traveling mapmaker, starting out in his native Switzerland, transplanting to Paris, then bringing his trade to America in about 1847.

The talented lithographer created various maps on U.S. soil — of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, New Orleans. They were part of a long-running series, “Bird’s Eye View.” Suffolk appears on an 1862 Bachmann map titled “Panorama of the Seat of War,” which North Suffolk’s William C. Wooldridge says would have been produced to meet an increasing demand for such easy-to-read pictorial maps sparked by the Civil War.

“Seat of War,” incorporating Virginia, Maryland, Delaware and the District of Columbia, shows Suffolk as a transportation hub at the head of the Nansemond River.

Wooldridge notes that two trains are on an apparent collision course, and ships with tall masts and billowing black smoke dominate the Chesapeake Bay.

Bachmann’s creation is part of a vast Virginia map collection that Wooldridge, a 69-year-old former attorney retired from Norfolk Southern railroad, assembled during more than half a century.

With more than 300 items, some that involve more than one map, it is regarded as the largest private collection of Virginia maps in existence.

Nothing is less than 100 years old, and Wooldridge says he bought many of the maps through dealers in New York.

“After I had been collecting a few years, the dealers recognized that I was interested in Virginia maps, and when they had something interesting, they would offer it to me,” he said.

“That continued for a couple of decades and more or less enabled me to assemble the collection.”

Wooldridge began collecting in 1970 while stationed in Heidelberg, Germany during a stint in the U.S. Army, after spying a “little map of Virginia” that set him back $35.

The collection is now in the hands of a society that half a dozen Hampton Roads businessmen formed to purchase the collection in its entirety after Wooldridge had put the word out that he was going to start offloading it.

The idea, Wooldridge says, was that the collection would be kept together and displayed publicly in a museum, rather than auctioned off piecemeal.

Required as part of the terms of the sale, he has put together a 392-page book on the collection, “Mapping Virginia: From the Age of Exploration to the Civil War.”

It features 355 illustrations, more than half in color, and a history of Virginia based on Wooldridge’s extensive research of the maps he collected.

“The narrative is about the maps, but it ends up being a history of Virginia from the standpoint of the mapmakers, which is a different take on things than you might find elsewhere,” he said.

For enthusiasts, maps, especially old ones, are more than depictions of the landscape for navigational purposes. Maps are commissioned by the victors and give insight into what drove them and how the modern era was forged.

“They are not just representative of geography, of the information that people had about geography … they are records of our history right from the beginning of the first settlement,” Wooldridge said.

“Many of them are just remarkably beautiful as art; the great century of classic map making was the 17th century, when the Dutch were the primary publishers.

“This was the age of Rembrandt; they just generated gorgeous maps, and they’re very visually appealing.”

As for the people who made the maps, “that’s a story in itself,” Wooldridge said.

Another map Wooldridge acquired showing Suffolk — none focus entirely on Suffolk — is Adolph Lindenkohl’s 1864 Military Map of Southeastern Virginia.

Lindenkohl produced the conventional map while in the United States Coast Survey.

“Both sides lacked adequate maps at the beginning of the Civil War, and in the North the people best equipped to remedy the deficiency were, like Lindenkohl, in the United States Coast Survey,” Wooldridge wrote in an email.

“The Coast Survey’s pre-war work mapping Virginia’s coasts and rivers gave it a head start in generating more detailed local maps for use by the Union army.”

Clearly intended for more practical purposes than Bachmann’s, Lindenkohl’s map is more akin to those of the modern age, with roads, railroads and natural features in much greater detail.

Chuckatuck gets a mention, as does the Jericho Canal in the Great Dismal Swamp, and four railroads converge in the downtown area of Suffolk.

Lindenkohl and his brother had immigrated to the United States from Germany, cumulatively spending more than a century drafting maps of their adoptive home.

Wooldridge’s book is available in Hampton Roads at the Mariners’ Museum, the Chrysler Museum, Prince Books and some Costco stores.