Labor of love

Published 9:17 pm Monday, January 30, 2012

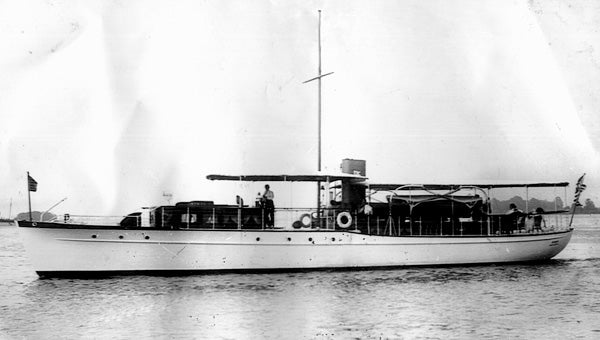

A beat-up old photo of the M.V. Nymph is one of only a few images Bill Keeling and Sam Wright have had available as they work to return the 75-foot wooden yacht to its original condition, circa 1913.

Eclipse man dedicates years to an old wooden boat

The air is thick with mahogany dust.

It has been trapped in the space by the blue tarps that hang over and around the entire area where Bill Keeling has been at work with an electric sander for a couple of hours.

It’s just another morning aboard the M.V. Nymph, a 75-foot Double Ender motor yacht built in 1913 by Matthews Boat Co. Keeling and Capt. C.J. “Sam” Wright, the project manager, have been restoring and rebuilding the old wooden boat for a client for three years.

Bill Keeling, a native of Eclipse, has worked on and around boats all his life, and a family that has included boat carpenters and homebuilders helped teach him about fine woodworking. Those careers come together as he works to rebuild and restore the Nymph, whose main salon will be a bright and airy place with gleaming mahogany when the project is done.

The work site is in a small boat storage and repair lot on Shipwright Street in Portsmouth, a dozen miles or so from Keeling’s workshop on Bleakhorn Road in Eclipse. The tarps keep the elements out and a bit of heat inside, but they also hide the scale of this project.

If the men stay on schedule — admittedly a daunting task for such a large project — by the time the yacht turns 100, she will look just as beautiful as she was the day she was launched in Port Clinton, Ohio.

Keeling expects that to be a big day in Eclipse, where the completed project finally will be unveiled.

“It’s going to be a show-stopper,” he says of the Nymph. “There’s nothing out there like it.”

And Keeling should know. Since 1995, he and Wright have partnered on two other complete restorations — Frolic, a 1939 44-foot Elco Cruisette, and Hiawatha, a 1937 53-foot Elco Commuter.

“It’s an enjoyable way to make a living if you’re crazy enough to do it and you’re not interested in making a lot of money,” Keeling says.

Between the major projects like rebuilding Frolic, Hiawatha and Nymph and the smaller ones like repairing the workboats and skiffs that are more common sights around Eclipse, Keeling has stayed busy working on boats ever since he came ashore from working aboard them as a waterman in 1995.

Born and raised in Eclipse, Keeling has spent his life surrounded by watermen and the tools of their trade.

Whether on the water or off, he has never been far from boats. A great-uncle was a boat carpenter, he says, and he remembers his father building a boat when he was a boy. In high school, it was his turn, and Keeling remembers learning about the important “scarf joint” during a project on an old wooden skiff.

“I love boats,” he says. “It’s all I’ve done all my life.”

Since retiring from the life of a waterman, though, he’s learned that he loves building boats more than running them.

“I enjoy problem-solving,” he explains. “This is just a series of problems.”

Which is a nice way of saying that restoring an old boat is an immense undertaking that is always more expensive and more involved than the owner or restorer can hope for.

When Keeling and Wright found Nymph moored in the Florida Keys, they knew she was the right yacht for their client, but they also knew that he’d want her restored to original condition. That would mean removing a superstructure that had been built above the deck; replacing most of the keels and stern stem; rebuilding cabins, decks and windows; replacing all of the electrical, plumbing, heat, water, engine and propulsion systems with modern ones; and reworking just about everything that remained.

“The owner wants it original, and I’m doing it as close as I can,” Keeling says.

All he’s had for guidance, though, are a couple of black-and-white photos and the original construction documents from 1912, which described many of the materials used but included no drawings or photos to show how they looked.

Just a series of problems.

Rebuilding a boat is by definition a long and arduous process. Keeling spent five and a half months on his knees replacing the northeast white pine deck boards, and without the modern invention of glue, he says, that work could have taken much longer. He regards his electric planer with a similar sense of appreciation for the time it has saved him.

But even with the help of technology, the work is done by hand — and sometimes without power tools at all. And rebuilding the boat still means confronting a series of problems, each of which requires a thoughtful solution.

“You can cut corners on a house, but once you cut corners on a boat, you’re taking risks,” Wright says.

For all the problem-solving, all the crawling around on hands and knees, all the sanding and planning and gluing and, eventually, varnishing — and with another year or so of work remaining — 66-year-old Keeling wonders if this will be the last big project.

“This one seems to be the retirement job, I think,” he says. “I’m too old to be working all the time.”

But then he turns to Nymph’s salon enclosure, with its broad-curved ends, places a rough and calloused hand on the mahogany he’s been sanding and begins explaining the difficulties inherent in rebuilding such a structure.

Wright grins and gives a slight, understanding shake of his head. “He’s crazy about these old wooden boats,” he says.