‘An Eye for an Eye’

Published 3:21 pm Wednesday, July 28, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Story by Phyllis Speidell

Photos by John H. Sheally II

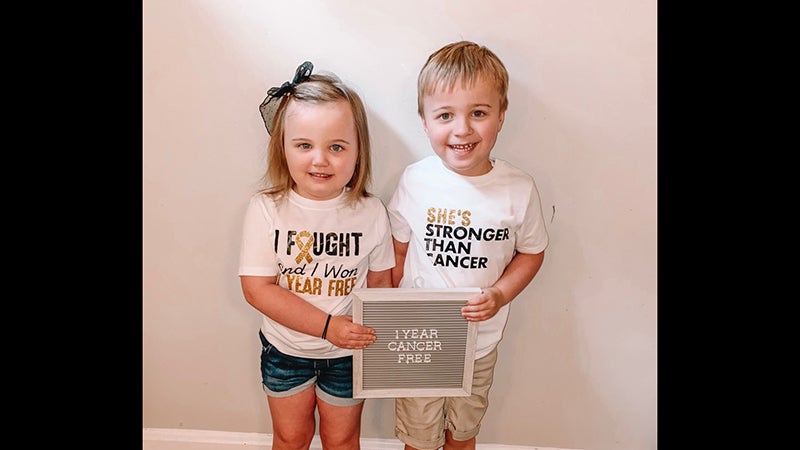

Ava Dunbar’s smile belies the array of medical treatments the 5-year-old has already experienced. Diagnosed with retinoblastoma (cancer of the retina) shortly after birth, Ava, at 14 months, underwent chemotherapy and ultimately had her right eye removed. Fortunately, her twin brother, Carter, one minute younger, had no trace of cancer.

Her mother, Blair Dunbar, still absorbing the shocking diagnosis, was grateful to have Ava’s life saved but fretted about her daughter growing up with an eye patch or an ill-fitting prosthetic eye. That concern was relieved by the artful craftsmanship of ocularist David LeGrand, a certified specialist in fabricating and fitting custom-made prosthetic eyes.

That complex art requires years of apprenticeship, a creative bent, painstaking attention to detail — and patience. Dunbar discovered that there are only two ocularists in Virginia and was happy to find LeGrand practicing in Western Branch, an easy drive from the Dunbar home in Hopewell.

LeGrand is part of the LeGrand Associates, a family business that has been creating prosthetic eyes for almost 70 years. He explained that glass eyes, as they were known then, were made almost exclusively in Germany and were in very limited supply post-World War II. In this country, makers of glass eyes turned to synthetics. American Army dental technicians boosted the effort by experimenting with methyl methacrylate, a material used in dental fabrications, as a material for prosthetic eyes.

LeGrand’s father, Joe LeGrand, was a teenager when his natural eye was injured. He was officiating a women’s basketball game when a player’s errant fingernail grazed his eye. In the 1940s, doctors evaluated the extent of an injury by introducing a stain to the eye. Unfortunately, LeGrand’s experience with a tainted stain left him with a deteriorating eye that was removed when he was in college.

Abandoning his dream of being an industrial arts teacher, he apprenticed with the eye maker who had created his prosthetic eye. The title “ocularist” had yet to be coined. Six months later, the eye maker went out to lunch and never came back. LeGrand took over for his suddenly retired mentor and established his own business in downtown Philadelphia. He discovered fierce competition among eye makers there — thanks, in part, to the proximity of Wills Eye Hospital, an international leader in ophthalmic care since 1832.

To survive, LeGrand expanded his business, opening as many as 40 branch offices along the Eastern U.S. and Canada. He trained 20 ocularists, including oldest son, Joe Jr. After the senior LeGrand passed away in 1983, the LeGrands consolidated into five offices, including one in Hampton Roads. David LeGrand, who had apprenticed with his older brother for six years after graduating from Slippery Rock College, moved to Virginia in 1996 to permanently man the office now in Western Branch.

The art of prosthetic eyes has been part of his life since he was 13 and helping in the business. His job then was to use a lathe to cut acrylic pieces that would subsequently be painted with irises.

Generally, he said, when an eye is removed, the surgeon will install a ball shaped orbital implant. The implant is attached to muscles in the eye socket enabling the prosthetic eye to move in unison with the patient’s natural, working eye.

Blair Dunbar noted that Ava’s prosthetic eye moves almost exactly like her seeing eye and few people notice the small differences.

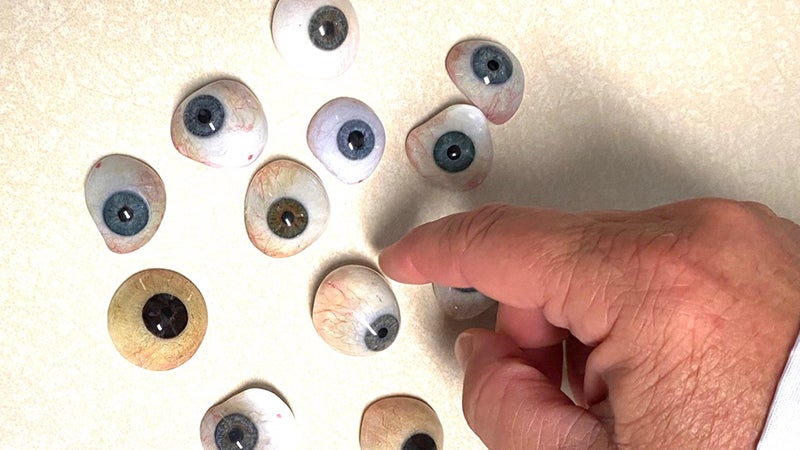

In his offices LeGrand keeps a lathe and tools with which he custom crafts eyes for each patient. He carves a wax model and, in most cases, takes an impression on the model. He mixes a synthetic and bakes it in the resulting mold to create the eye form. From there he meticulously matches the prosthetic eye to the patient’s natural eye, matching colors and shading and even replicating the eye veins with a red pencil or applied fine embroidery floss. A final gloss coat brings the acrylic eye to life.

LeGrand also crafts eye shells, synthetic shells to slip over blind, deteriorating eyes for cosmetic reasons.

Some patients have requested a custom eye or shell with a wolf eye, a cat eye or even an NFL team logo.

Generally, those are spare eyes, with the patient also having a traditional, realistically designed eye — “something appropriate to wear to grandmother’s funeral,” LeGrand said.

Synthetic eyes have advantages over the old glass eyes. They are lighter and more durable. LeGrand recalls the story of an electrician working at the top of a crane when he lost his prosthetic eye. The synthetic eye survived the 50-foot drop unscathed.

Generally, patients can wear a prosthetic eye for about a month and then remove it for cleaning. Blair laughed as she recalled a teacher overhearing Ava boasting to a few classmates that her eye was not only beautiful, but she could also take it out and put it back in.

There are misconceptions about prosthetic eyes. People think the fitting process will be painful or insurance will not cover the cost of an eye. They don’t realize, LeGrand said, that nothing he does is painful, how good a prosthetic eye can look or that insurance generally covers part of the approximately $3,900 base price cost of a prosthetic eye.

“People hang on to a blind eye for so long out of fear,” LeGrand said. “When they finally get a prosthetic one, they say ‘I should have done this 10 years ago.’”

LeGrand is passionate about his work and has made about a dozen mission trips to Haiti with the New Creation Methodist Church in Western Branch, other Methodist churches and with the i-Team. The 20-year-old i-Team built an eye care clinic on the St. Louis du Nord campus of the Northwest Haiti Christian Mission.

His home and work remain, however, grounded in Hampton Roads.

After a year of searching for a home in Hampton Roads, the LeGrands, in 1996, were introduced to the wider Churchland area by a patient who lived there.

“She fed us ham biscuits and sweet tea and showed us around,“ LeGrand remembered. “We found a home here.”