The Nansemonds Now

Published 8:08 pm Thursday, June 3, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

STORY BY PHYLLIS SPEIDELL

PHOTOS BY JOHN H. SHEALLY II

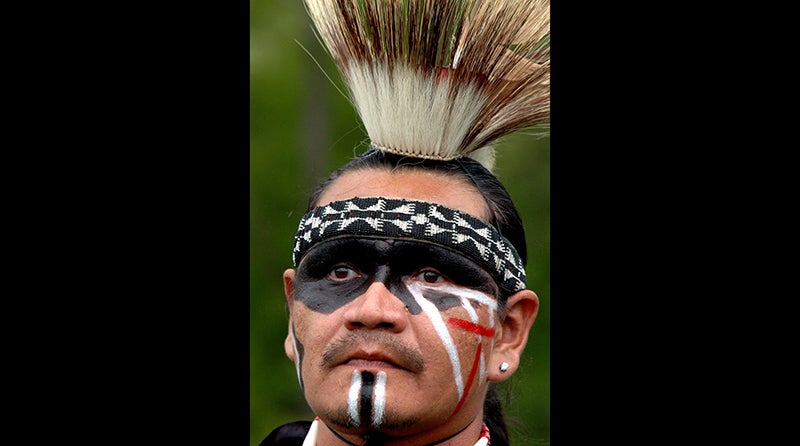

Three years after the Nansemond Indians received federal recognition, the tribe, now officially the Nansemond Indian Nation, continues to gain momentum.

But beyond a name change, what does federal recognition mean? How does it benefit the tribe that pushed so long and hard to gain that acknowledgement?

According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a federally recognized tribe, as a sovereign entity, has a government-to-government relationship with the United States and is eligible for certain federal funding, services and protections. Currently there are 574 recognized American Indian Tribes and Alaska Native Villages.

As to what that means for the Nansemonds, Chief Earl Bass is happy to share a long list of strides — almost all enabled by federal recognition — the tribe is taking now in community interaction as well as tribal development and support.

While some other Virginia tribes have announced proposals to develop casinos and entertainment venues, the Nansemonds, Hampton Roads’ only surviving indigenous tribe, focus on cooperative educational and environmental community projects as well as programs to improve the quality of life for tribal members.

Earl Bass, who previously served as chief of the Nansemonds, was persuaded to return to the position and voted in by the tribal council, starting his current term in January 2021. Keith Anderson, a retired administrator with Virginia Beach Parks and Recreation, serves as assistant chief and environmental program director.

“At the first meeting between the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the six Virginia tribes who recently received federal recognition, we were told to open our mouths wide as the information was going to come at us like a fire hose,” Bass said. “They were right. The amount of information was mind-blowing, so much to digest.”

“As a former chief, I had just gotten to where I was sleeping well at nights,” Bass added. “Now, as chief, my head hits the pillow and tribal business starts running through my mind.”

Bass and his wife, Loleta, a retired nurse, were surprised at the flood of paperwork, meetings and opportunities. Loleta understated their lifestyle now with an emphatic “busy!”

Finding their way through a bureaucratic maze of government and non-profit organization grants and programs enabled the Nansemonds to accomplish many of the goals they, for years, had hoped to achieve.

Tribal officials combed the membership rosters, attempting to contact long-missing members, sorting out the deceased and opening membership to families of tribal members. Currently the Nansemonds number 409 individuals.

Through the HUD (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development) Native American program, the tribe was eligible for annual grants enabling them to buy and renovate three townhouses in the Westhaven section of Portsmouth. The homes shelter tribal members in need of housing or are rented to generate income. Rental and mortgage down payment assistance programs may be in the future as well for tribal members.

The Nansemonds purchased 17 acres on Route 17 in North Suffolk to potentially use as a meeting place, a clinic, or as housing for tribal members.

Through the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act, the tribe was able to furnish computers and hot spots to members who needed them to continue their education.

Through the Indian Health Service of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the tribe now can assist members with doctors’ visits, prescriptions and some other medical costs. That program also enabled the tribe to provide COVID-19 vaccinations for 100 members as well as some members of the community.

The tribe, always active environmentally, is working to restore the oyster beds in the Nansemond River and, also, according to Anderson, working with Ducks Unlimited and Dominion Energy to conserve 504 acres of land in Driver. The land will be given to the tribe who will, in turn, place it in a nature conservancy.

Purchase and preservation of the historic Indiana United Methodist Church in Bowers Hill, the spiritual home of the Nansemonds, is another future hope for the tribe. Already listed on the Virginia Landmarks Register, the property is under consideration by the National Park Service for the National Register of Historic Places.

In 2019, the Nansemonds introduced the Firebird Festival, an annual public event created to share the Nansemond history, language and culture. The festival components are based on Virginia’s fourth-grade Standards of Learning guidelines and encourage children — and adults — to learn more about Native American heritage directly from the source.

Bass and Anderson both stress that the tribe wants to nurture its cooperative relationship with the city of Suffolk via future programs, possibly at Lone Star Lakes Park, adjacent to the Nansemond replica village of Mattanock Town, and, ultimately, a Nansemond-sponsored community center open to the public.

Mattanock Town sprang from a 2013 agreement between the tribe and the city of Suffolk to set aside 77 acres of city-owned land on the Nansemond River. The Nansemonds planned to develop a replica village and cultural museum there, where they have hosted their annual powwow for 30 years. If, after five years, the tribe’s plan was successful, the city agreed to deed the land over to the Nansemond Indian Nation.

Since then, the tribe has cleared two and half miles of trails and built a pair of longhouse shelters typically used by early Nansemonds who lived in familial villages along the river. They remodeled the existing lodge building on the property and set up a food bank for tribe members. Start-up funds from the federal recognition enabled them to buy a 12-person van and buy and equip a modular building to use as an office. To install Wi-Fi in Mattanock, the tribe paid to have the internet access brought down Pembroke Lane from Route 10, benefiting residents along the lane as well.

There is much more, Bass and Anderson said, that can be done for the tribe — and the city — with funding that federal recognition generates. The Bureau of Indian Affairs has a highway department that will provide up to five miles of entry road to Mattanock from Route 10 as well as other roads on the property. The tribe wants to create a canoe/kayak landing on Cedar Creek on the Mattanock property as well — a project that could be funded by the CARES Act.

According to Bass, however, those newer projects require that the Nansemond Indian Nation hold the deed to the Mattanock property. Three years after the original five-year deadline, the tribe continues to make significant progress in developing that property. Bass, Anderson and the rest of the Nansemond Indian Nation remain hopeful that the city will see its way clear to convey the Mattanock property to the Nansemond Indian Nation.