A Suffolk native on the Alaska Highway

Published 3:56 pm Monday, April 6, 2020

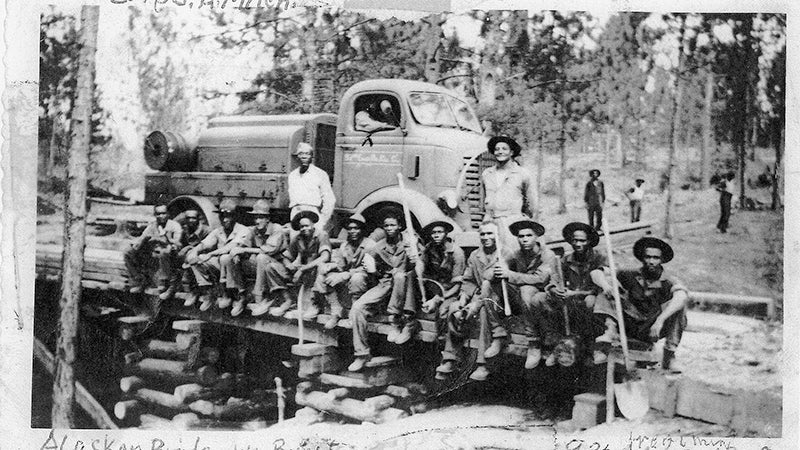

- Soldiers from the 93rd Engineer General Service Regiment posing on a bridge they built; Suffolk’s James Ausby Mitchell is in the truck. (submitted photo)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The world was at war in 1942, and the United States was deeply embroiled in it, with emotions raging following the late-1941 attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese.

The territory of Alaska, with its Aleutian archipelago stretching across the deep blue sea almost all the way to Japan, was considered a vital part of the nation’s defense from the Axis Powers. As part of the strategy to defend Alaska — and therefore the rest of North America — the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was dispatched to build a land route to Alaska through extraordinarily difficult terrain.

The soldiers encountered hostile working conditions both winter and summer. In the winter, they struggled to build roads through permafrost and muskegs, generally known as swamps or bogs. They battled temperatures far below zero and the resulting frostbite, and many soldiers died. During the warmer months, voracious mosquitoes and gnats attacked the soldiers as they worked.

Of the 11,000 soldiers working on the project, more than one-third were black, according to “We Fought the Road” by Christine and Dennis McClure. White regiments took the credit, and the black soldiers’ contributions were not well known until more recently. White regiments were featured in photographs, films and news reports of the time, while the black ones were ignored, the McClures wrote. The black soldiers had to build barracks for the white ones, while they slept in tents.

One of the regiments working on the project was the 93rd Engineer General Service Regiment. One of the soldiers toiling in it was Suffolk native James “Bud” Ausby Mitchell.

The 93rd arrived in Skagway on April 14, 1942, according to “We Fought the Road.” They completed their section of highway on Oct. 10 that same year, and the entire highway was dedicated on Nov. 20.

The men of the 93rd, Mitchell included, established water points, built and repaired roads and bridges and culverts, constructed POW facilities and more. They faced all of the same challenges as the white soldiers, only with prejudice on top.

Mitchell drove a truck, operated earth-moving equipment and helped build bridges. In all, the construction of 1,600 miles of highway took only eight months and 12 days.

Mitchell’s legacy lives on, not only on the Alaska Highway but more importantly here in Suffolk. He and his loving wife, Terease E. Mitchell, raised 10 children: Beulah M. Robertson, William Boyette Jr., Ceylon N. Mitchell, James T. Mitchell, Arvis L. Hall, Connie P. Gay, Dedra O. Mitchell, Kathy L. Hart, Ausby N. Mitchell and Lynn T. Parker. His brother is the well-known “Mr. CIAA,” Abraham Mitchell. He also has numerous grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren. He went on to work in the Naval Yard in Portsmouth and died in 1981.

His son, Ceylon, retired from the U.S. Air Force after 24 years of service and lives in Alaska, did much of the research on their father’s service.

Mitchell’s DD-214 tells the details of his service. He was in for three years, 11 months and 23 days, from August 1941 to August 1945. He earned the American Theater Service Medal and the Asiatic Pacific Service Ribbon. After the 93rd moved to the Aleutians in 1943, Mitchell was injured by exploding ordnance and came home with a limp, according to a website run by the McClures, www.93regimentalcan.com.

But what it doesn’t tell is what the family knows about his legacy — how his work ethic and faith in God got him through the difficult work in the Yukon and Alaska wilderness.

“He talked about how cold it was,” said Arvis Hall. “His toes and fingers were frostbitten (when he came home on leave). He said he hated to go back, but he knew he had to finish the highway.”

That was a part of his character, Hall said, and he passed it down to his hardworking children.

“He never started anything he didn’t finish, and he brought us up the same way,” she said. “My dad had the fortitude, and he took God with him everywhere he went.”

Daughter Kathy Hart also honored her father for his hard work and character.

“Our dad was a proud man,” she said. “He instilled in us that we were never to ask anybody for anything and to work to get your own, making it impossible for anybody to take what you earned away from you. We salute him and will always remember to share his legacy to all generations.”

Hall said their father will always be their father, but it’s great to know he and his comrades are finally getting the credit for something that was greater than the sum of all of their parts.

“It just brings tears to our eyes,” Hall said. “Realizing the impact of something that big — my dad did that in Alaska. It’s amazing my dad was part of that.”