The canaries of Penniman

Published 5:44 pm Thursday, July 12, 2018

- The history of the town of Penniman was researched by Suffolk resident Rosemary Thornton for her book. (Photo by John H. Sheally II)

Story by Phyllis Speidell

Photos by John H. Sheally II

A century ago, a small town sprang up on the shores of the York River, thrived for half a dozen years, and then faded into obscure Virginia history.

E.I. duPont de Nemours and Company built the town in 1916 to accommodate the 5,000 munitions workers (mostly women) and 6,000 laborers recruited from all over the Southeastern United States to work there in its new munitions plant. DuPont named the town Penniman, in honor of Russell S. Penniman, a company scientist who invented “Extra Dynamite,” an ammonium-based dynamite considerably more powerful and economical than traditional dynamite.

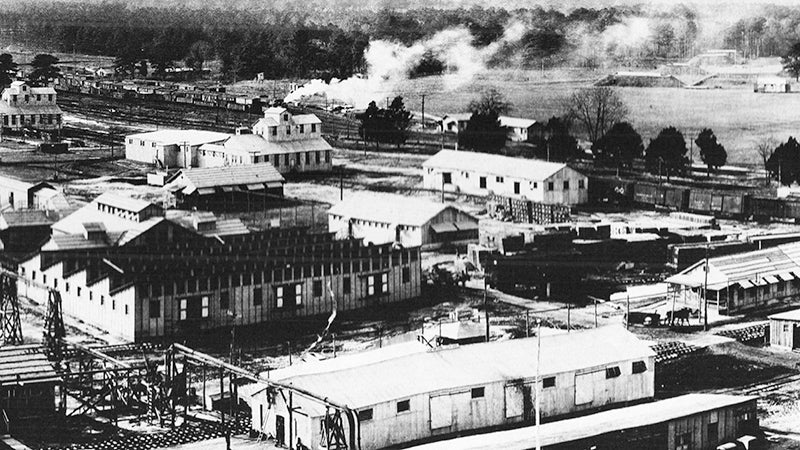

DuPont originally built the plant to manufacture dynamite but spent more than $11 million to expedite converting the original facility to a preeminent munitions plant when the U.S. entered World War I in 1917. Shell storage magazines, warehouses and a changing facility where workers donned safety clothing, supported the eight shell-loading lines and the “booster plant” and were all connected by new rail lines.

The town included 200-plus single-family homes and apartments, as well as bunkhouses and dormitories for the single workers. Restaurants, a hotel, shops, police and fire stations, a hospital, jail, bank, post office, rail station, YMCA and YWCA rounded out the town amenities on 6,000 acres about six miles from Williamsburg.

Rosemary Thornton, Suffolk resident, author and architectural historian, uncovered the almost forgotten story of the plant and town and documented it in her book, “Penniman, Virginia’s Own Ghost City.” Impressively well researched historically, the book also captures the energy and life style of Penniman’s resident workers who braved isolation, toxic materials and even the Spanish flu to fulfill what many of them considered their patriotic duty.

Rosemary Thornton is a Portsmouth native who now lives in Suffolk and has extensively researched 20th-century residential architecture. (Photo by John H. Sheally II)

The Penniman story also has a few ties to Suffolk.

DuPont’s first choice for its new plant had been historic Jamestown Island, decades before historians authenticated that area’s connections to Capt. John Smith and the first permanent English settlement. Thanks to a feisty elderly widow who refused to sell her land there, the company crossed off the island site and looked south — to the village of Driver in what was then Nansemond County, now Suffolk.

In March 1916, area newspapers reported that DuPont engineers were scoping out the Driver area, and rumors spread of DuPont seeking options on local farms. Later that month, however, DuPont announced its site selection as the land we now know as Cheatham Annex. As the U.S. entered the war a year later, much of the Atlantic Fleet would be stationed close by in the York River.

Within three months, the York riverfront was bustling with construction workers as what locals nicknamed a “toadstool town” seemed to mushroom overnight. Until Penniman was up and running, those laborers commuted by rail to the construction site from whatever quarters they could find to rent in the suddenly overcrowded town of Williamsburg.

DuPont, the U.S. government and the U.S. Army contracted to have the new shell loading plant and town productive by December 1918 and agreed that the completed heavy artillery shells would not be stored on site but shipped out immediately to the front lines. Operational on June 20, 1918, the plant worked to meet a monthly production of 625,000 75mm shells, 300,000 155mm shells and 100,000 8-inch shells as well as 1.2 million boosters. The shells ranged in size from 20 inches tall and 15 pounds to over 100 pounds. Many of those shells were barged to the former Army Pig Point Ordnance Depot in Suffolk (adjacent to the present upscale Harbour View development) to be shipped from there to the front lines.

Canaries “Stuff one for the Kaiser”

While construction continued, so did the process of recruiting munitions workers to load and finish the shells. Women were, Thornton said, the then-obvious choice because so many men were in the military, because women had smaller hands, well suited to packing powered TNT into the shells, and because women were thought to be mentally more suited to repetitive tasks.

Female recruiters extolled the pleasures of life in the new riverfront town of Penniman and a starting wage of 45 cents an hour. They encouraged women to step out of their traditional roles to work at the plant and support their “boys at the front.” “Stuff one for the Kaiser” became the recruiter’s rallying cry.

The recruiters glossed over the military barracks-style dormitories, the round-the-clock eight-hour work shifts and the perils of the work — the potential danger of massive explosions, an outbreak of the deadly Spanish flu and the risk of TNT poisoning.

At Penniman, powdered TNT, Amatol (molten TNT) and Tetryl were used to load artillery shells and boosters. The TNT, as finely powdered as talcum, presented the additional hazard of TNT poisoning that could stain skin, hair and nails a dark yellow and turn lips purple, inspiring the nickname “canaries” for the mostly female workers. The canaries could also develop blood cell damage, nausea, dizziness, nasal and throat pain as well as possible liver problems, sterility, bone marrow damage, jaundice and more. The poisoning struck often. Penniman medical personnel recommended thorough bathing, enemas and diuretics as well as drinking large amounts of warm milk to alleviate some of the symptoms, but the long-term effects of the toxins were undetermined.

Undaunted, women of all ages, backgrounds and marital status, eager to do their patriotic duty, jumped aboard trains heading to Penniman to join the work force. Much like the better-known Rosie the Riveters of World War II, the women, clothed in mandatory khaki “womanalls” and rubber-soled oxfords, labored on the lines, loading shells until the plant closed.

The war to end all wars

With the Nov. 11, 1919, armistice that ended the war that supposedly was to end all wars, the plant shut down rapidly. DuPont and the government discharged the Penniman production employees, and in June 1920, began dismantling the plant and town, eventually scrapping or auctioning off the buildings and equipment.

The remaining shells, 400,000 of them, went to the highest bidder, a salvage firm whose laborers used high-pressure hoses at the Penniman site to wash explosives from the reclaimable brass casings.

Numerous buildings were auctioned, disassembled and rebuilt at new sites including the College of William & Mary, which was gearing up for an influx of postwar students. Some enterprising contractors reconstructed homes from Penniman on new sites near Williamsburg.

Two ingenious, entrepreneurial, stevedore brothers, Bert and Gary Hastings, bought three dozen of the Penniman houses and floated them, intact, on barges downriver, two at a time, to Newport News and to Norfolk’s Riverfront, Ocean View, Willoughby Spit and Larchmont. Another stevedore, George Hudson, brought 20 of the Penniman bungalows and moved them to Norfolk as well. At least nine of those small bungalows found new sites on Ethel Avenue in Norfolk and inspired Thornton to investigate their lineage. That research led her to the story of Penniman.

Gone but not totally forgotten

In 1942, the U.S. government, ramping up its participation in yet another world war, picked the former Penniman site for an East Coast naval supply depot, Cheatham Supply Annex.

“I felt an abiding duty — even a calling — to share the story with other people who wanted and/or needed to know of the Pennimanites’ sacrifice,” Thornton said. “This is the story of people who served honorably during a difficult and dark time in our nation’s history.”

About Rosemary Thornton

Originally from Portsmouth, Rosemary Thornton graduated from I.C. Norcom High School where she took courses in auto mechanics. After running a successful appliance repair business for years with her husband in Western Branch, Thornton moved to St. Louis for 10 years, divorced and returned to Hampton Roads, where she remarried and settled in Norfolk. Just over a year ago, Thornton relocated to North Suffolk.

Intrigued by the kit houses popular in the early 1900s, she studied and wrote extensively about the Sears, Aladdin, Montgomery Ward and other mail order kits that enabled would-be homeowners to affordably build their own homes — following step-by-step directions with pre-cut parts. A recognized expert on the subject, she has written and co-authored half a dozen books, been featured in numerous magazines and newspapers and has lectured across the country.

Her knowledge of early 20th century residential architecture and her curiosity about the small bungalows along Ethel Street in Norfolk led to her most recent book, “Penniman: Virginia’s Own Ghost City,” which is available from Amazon.