Hard truths about the Ironclads

Published 10:19 pm Wednesday, June 13, 2018

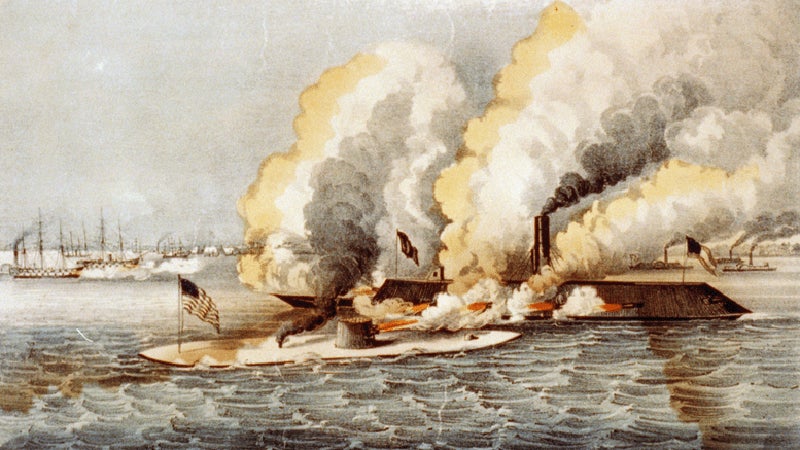

- First published by Currier & Ives, this painting of the battle between the U.S. ship Monitor and the Confederate ship Virginia shows the many other ships that were awaiting opportunity to help. (Courtesy Photo)

The Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel between Newport News and Suffolk is named after the historic “Battle of Hampton Roads,” but as Dan Wood told the crowd of 20 history buffs at the Suffolk-Nansemond Historical Society Wednesday afternoon, it should be called the “Misnamed Monitor Merrimac Bridge Tunnel.”

“The Monitor never fought the Merrimac,” Wood said quickly and earnestly while wearing his Mariners’ Museum polo. “They were both U.S. Navy ships, and the Merrimac was in fact a three-masted wooden frigate.”

Wood has been a volunteer at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News for eight years. His presentation for Suffolk Public Library’s series of Afternoon Conversations detailed the 1862 Civil War battle, also known as the “Battle of the Ironclads.” He wanted to focus on the overall history of ironclad warships both at home and abroad.

“A lot of people know about the Monitor and the Merrimac — more properly the Monitor and the Virginia — but the majority of people have no idea that they were just the tip of the iceberg,” Wood said.

There were more than 100 ironclad warships between the Union and the Confederates, depending on your definition of “ironclad.” In simplest terms, they were armored warships, but the definition of “armor” varies. In the 1864 Battle of Cherbourg, the U.S. Navy warship Kearsage had cables along her port and starboard midsections for makeshift chainmail.

“Mountains and hills, where do you draw the difference,” Wood asked his audience. “If you talk about the Blue Ridge Mountains to somebody from Colorado, they’d laugh at you. There’s no authority of who defines these things. So it is with armor.”

The earliest recorded use of “ironclad” warships, according to Wood, was in the Sea of Japan in 1592. During the Japanese invasions of Korea, the outmatched Korean Navy managed to fend off Japanese wooden ships on several occasions using relatively smaller ships that were armored on top and equipped with cannons.

Korean Admiral Yi Sun-Shin became a national hero thanks to these “turtle ships.”

“They were highly maneuverable, very well armored, and they even had a dragon head on the bow that breathed fire,” he said.

It was the kind of ingenuity the Confederates needed to break the Union blockade in 1862 that cut off Virginia’s largest cites and industrial centers from international trade. They needed aid from international allies, but first they needed a Navy. They found an opportunity when they took Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth: the USS Merrimack, which has come to be spelled without the final letter in most uses.

“The Merrimac at that time was one of the six newest and most powerful ships in the U.S. Navy,” Wood said.

The Merrimac had been destroyed before the Confederates arrived. They salvaged the remains from the Elizabeth River for their own ironclad, the CSS Virginia. Flag Officer Franklin Buchannan began the historic battle on March 8, 1862, when he and his crew aboard the Virginia decimated the Union blockade.

According to Wood, the Virginia sank two major U.S. warships on its maiden voyage and damaged another. Three Union transport ships were lost. The U.S. Navy casualties numbered at 369, with minimal damage to the Virginia.

“This would be the worst single day in the Navy’s history until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor,” Wood said.

But word had traveled in the year prior that the Confederates were building this heavy hitter. The Union commissioned the Ironclad Board in August 1861 to build an opposing ship, which eventually became the USS Monitor, based on the designs of Swedish engineer and inventor John Ericsson.

It was a leaner, more efficient beast compared to the Virginia, at about two-thirds the size and one-fifth the guns and crew.

“It was equal or superior to the Virginia basically in every way,” Wood said.

The two armored warships converged off the shores of modern-day Suffolk on the morning of March 9, 1862. Their cannons fired for more than four hours, but neither ship sustained significant damage. The Monitor merely had two dents from the USS Minnesota at its back, a minor case of friendly fire.

The duel ended with the Virginia returning to the Gosport Navy Yard for repairs and the Monitor holding its post. The blockade didn’t falter.

“In my mind, the Monitor won that battle by the fact that they were still afloat at the end of the battle, and for the next two months they kept the Virginia in check and kept Hampton roads open for the Union,” Wood said. “Whether they sank the Virginia or not, they contained that threat.”

Navies in England, France and the rest of the world were already developing their own ironclad fleets when news of the battle traveled, but it inspired further invention and reinvention nonetheless. Rams were brought back to the fore after they did major damage in Hampton Roads, and newly developed turrets that could move independently became must-haves on nearly every vessel.

“The day Emperor Napoleon III from France found out about the results of the Battle of Hampton Roads — literally that day — he canceled something like 30 contracts that were out to build wooden warships for the French,” Wood said. “From then on, nothing but iron ships.”

By the end of 1865, 12 other countries had 45 sea-going ironclads in service, with 36 more near completion, all of which was superior to anything in the U.S. Navy at the time, Wood said. Improvements to the U.S. Navy wouldn’t occur for more than 20 years after the Civil War.

Think about that the next time you’re stuck in traffic in the MMMBT, especially on the Newport News side of the tunnel, where most of the eponymous skirmish happened.

“Next time you go through the tunnel, look up and you’ll have a real good view of where the battle took place,” joked Wood.