Shining a light

Published 9:33 pm Monday, March 17, 2014

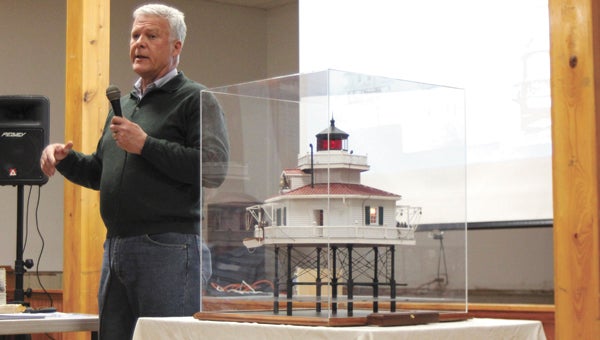

Larry Saint presents his scale model of the Nansemond River Lighthouse to a packed house in at the CE&H Ruritan Hall in Eclipse.

Spend countless hours building a scale model of a lighthouse that was almost lost to history, and you probably would want to exercise extreme caution around table edges.

Larry Saint, a financial adviser from Smithfield who used to live in Suffolk’s Sleepy Lake neighborhood, is fortunate he learned this lesson early in the proceedings — though he learned it the hard way.

The lighthouse that warned mariners of danger a few feet beneath the surface was located near the mouth of the Nansemond River, north of Pig Point and east of Barrel Point.

Like the other five lighthouses on the Lower James, which lit the way from the mid-1800s through the 1930s, it didn’t look like your stereotypical lighthouse — those of the Outer Banks, for instance.

This photo of the Nansemond River Lighthouse, credited to Maj. Jared A. Smith and dated May 21, 1885, is kept at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News.

But before Saint started on his half-inch-to-the-foot model, most folks knew much less about what the Nansemond River Lighthouse and its siblings looked like. The tide of history had ebbed.

Saint presented his model during a recent installment of Suffolk River Heritage’s River Talk, held at the CE&H Ruritan Hall in Eclipse. He now plans to put together a book on the topic with Phyllis Spiedell, John Sheally and Karla Smith, a trio that has been chronicling local history in an ongoing series of publications.

A chance encounter at Smith’s house with the original lighthouse plans set Saint on 18 months of researching and building.

Smith, chairman of the heritage group, said she obtained the diagrams from a friend who worked for Ron Pack, developer of Smithfield Station. Pack, Smith said, had tracked them down from the Coast Guard, for architectural design purposes.

“I started with Karla’s plans, did research, and set out building it,” Saint said.

He started with the pilings, in the same way crews constructing the actual lighthouses did when they used capstans to “screw” the piling foundations of the screw-pile lighthouses into the riverbed.

“It took me a while to get the turnbuckles and the supporting cables correctly to scale,” Saint said.

It was about at this point that a sickening turn resulted in a lesson learned.

“I stupidly set it on the side of the bench. I turned around to do something else, and it fell off,” Saint reported. “I had to start all over again.”

But Saint came back stronger, and the completed model features decking, a central spiral staircase, windows with shutters and interior shelves. He even miniaturized the rope-and-pulley system lighthouse keepers would use to hoist the launches they used to ferry between their workplace and the shore.

He described how modeling the Fresnel lens — Frenchman Augustin Fresnel’s 1822 invention that revolutionized lighthouses with greatly improved efficiency — was one of the greatest challenges. Saint overcame it by turning a scale version from basswood, creating a mold from it, then doing a resin pour.

While many hobbyists would have been content to just build the model, Saint visited the National Archives in Washington, D.C., digging up a plethora of information on all the lighthouses of the Lower James, which also include Deepwater Shoals, Point of Shoals, White Shoal, Middle Ground and Craney Island.

He also scoured secondary material, piecing together the history of lighthouses down the ages to the Pharos of Alexandria.

The Nansemond River Lighthouse cost $15,000 to build in 1878, according to Saint. It was positioned at a point where shoals altered the depth from 25 to only two to four feet. Light first shone out from its kerosene lamp on Nov. 1, 1878.

Though the fact it was built after the Civil War spared the Nansemond River Lighthouse, Confederate raiders disabled the James River lighthouses that did exist then, for the purpose, Saint said, of putting Union mariners on the back foot. Rebel forces had the local, inside knowledge of where shoals lurked, whereas the Yankees were much more disadvantaged by darkness.

Saint also researched lighthouse keepers, and they apparently weren’t in it for the money or the lifestyle. For instance, Saint said, Rufus Potter received an annual salary of $575, the equivalent of $14,000 today. But they also were provided room and board.

Saint was able to document six keepers of Nansemond River Lighthouse through 1911, including Ella Edwards, who took over from her late husband.

The lighthouse keeper’s life, according to Saint, included monthly inspections and keeping the lighthouse clean and orderly.

In winter, a fire roaring in the potbelly stove in his small room was not enough for a lighthouse keeper not to see his breath, according to reports, and ice floes — often responsible for the demise of the lighthouses — made the structures shudder and shake.

“It was a tough life for them,” Saint said.