Signing the night away

Published 10:49 pm Monday, January 20, 2014

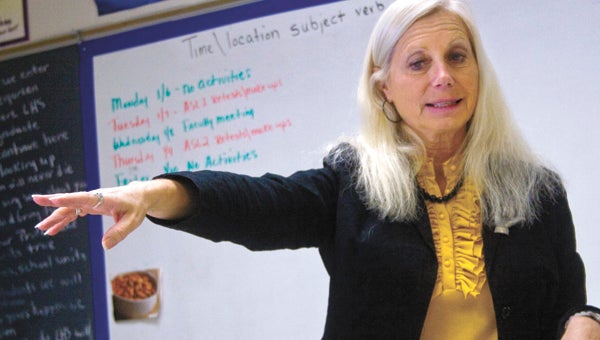

Anita Fisher, who teaches American Sign Language at Lakeland High School, gestures during a review after school for a small group of students preparing for a make-up quiz.

Fast-food eateries on busy Saturday evenings aren’t the quietest of places. But a pocket of silence holds court in Chick-fil-A on North Main Street, drowning out the clamor.

On a vacant table inside the front door, a sign written in pen on a nutrition guide proclaims: “Reserved: Silent Dinner.”

It’s a rainy December night, and only the second installment of the twice-monthly event, started by Suffolk Public Schools American Sign Language interpreter Candice Gallop and special education student teacher Ella Mae Anderson.

They did so at the urging of Lakeland High School ASL teacher Anita Fisher, a friend of theirs from Southside Baptist Church who’d planned to start the group herself but didn’t have time.

“Suffolk had nothing for our deaf population” before the group, Gallop said, explaining folks would drive to Norfolk, Virginia Beach, sometimes even further.

Sitting across from her, Ella Mae’s husband, Bryan Anderson, reads a newspaper. Sarah Bowyer, 17, Fisher’s student at Lakeland High, shares a set of booths with the home-schooled Miller kids: Katie, 14, Alicia, 13, and Donnie, 17.

“When I grow up, I want to at least have a job as an (ASL) interpreter,” says Alicia.

The 10 or so eloquent pairs of hands are amiably signing the evening away over chicken sandwiches and sodas.

Presently, wearing a Chick-fil-A uniform, Neil Phelps joins in. He says he took ASL in high school, because he needed a language for an advanced diploma, which Fisher says is why a lot of her students take the subject.

“I just fell in love with it and stuck with it.” Phelps said.

Fisher is proud of Gallop and Anderson for fulfilling her vision by starting the monthly dinners. “They did a very good job,” she said.

When she discusses former students who’ve continued studying ASL beyond her classroom, Fisher gets emotional.

“It’s a joy beyond anything I could ever want,” she said recently, just before the tears began.

“When I see them” pursue ASL at college, “and I have had a little bit of influence on them to go, I’m just happier than words could express.”

Fisher’s opportunity to learn the silent music of signing and become a qualified instructor was born of adversity, or at least a family setback: In Pennsylvania in 1997, the law firm her husband worked for laid him off.

“The kids started college, and I was chief everything,” Fisher said.

Her husband suggested she might like to improve her earning potential by taking a course, and Fisher decided to indulge a latent interest in sign language.

At Mount Aloysius College in central Pennsylvania, she studied under a professor whose son was deaf. “She just showed the love in the language, the love of the people, and she made me fall in love with it,” Fisher said.

Those were continuing-education classes. Fisher commenced college-level classes at Mount Aloysius in 1998, graduating at the turn of the millennium with an associate’s in interpreting.

With that, she was able to work as a substitute interpreter while working toward a degree in deaf education at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, graduating in 2003.

By the time Fisher chanced across Suffolk Public Schools — and the prospect of becoming an ASL teacher — at a Pittsburg job fair, her husband had found a good job with the multinational Siemens and escaped unemployment.

It could have been a complicated situation.

Fisher went home and told him, “Would you like to move to Suffolk, Va.?” He said, “Where’s that?” Fisher said, “I don’t know.”

After consulting an atlas, learning Suffolk is an easy drive to the beach and praying for guidance, the Fishers plunged into new, warmer waters.

Arriving in Virginia, it took her husband nine months to find a job, and it still “wasn’t the one he wanted,” Fisher said. (He now happily works for a private technology firm contracting with the Navy.)

The Suffolk move led to their son Seth’s introduction to lacrosse, which he now plays at Shenandoah University. “We didn’t have lacrosse where we were before,” Anita Fisher said.

Fisher had four classes and about 90 kids when she started with Suffolk Public Schools in 2003. She now has six classes, including three ASL 1, two ASL 2, and one ASL 3, and 153 budding signers.

ASL is so popular, they turn kids away, she said. Fisher’s ASL education colleagues within the school district are Rebecca Carter at King’s Fork High School and Cleo Dickinson at Nansemond River High School.

As Phelps at Chick-fil-A demonstrated, students need a foreign language for an advanced diploma, and ASL meets that requirement.

Kids think ASL 1 will be a home economics-like easy ride, Fisher says, but soon learn they’re mistaken.

“Some kids will decide (they’re) still going to learn it, and do quite well,” she said; however, “It’s not easy just because it’s not spoken: You still have to memorize. You still have grammar rules; you have different things that spoken language doesn’t have. You have facial expressions that are the adverbs. You have sounds.”

Fisher said its practicality also draws students to ASL — the need to communicate with a deaf person in Suffolk is arguably greater than with a foreign language speaker with no English, for instance. And, like she did, they fall in love with it.

As the drizzle outside Chick-fil-A continues, the first deaf person of the evening joins: 25-year-old MeMe Bennett. Gallop said another deaf individual, a Zuni woman, attended December’s inaugural dinner.

The woman’s husband, who never learned to sign, came with her. The experience gave him insight into what it’s like for his wife when he’s conversing with friends and she can’t understand what they’re talking about, Gallop said.

The plan is for the silent dinners to continue the second and fourth Saturday of every month, Gallop said, from 6 to 9 p.m.

Attendees don’t need to be connected to Southside Baptist Church or current or former ASL students at Suffolk Public Schools, she said.

“We want it to be open to everyone.” ←