The father of Mr. Peanut

Published 10:52 pm Friday, October 18, 2013

From left, Charlie Lewis, Bob Slade and Peyton Lewis, nephews of Mr. Peanut creator Antonio Gentile, show off the original drawings by their uncle, a Suffolk native, that transformed into one of the world’s best-known advertising icons.

Antonio Gentile was more than just that, nephews say

He’s one of the most recognized advertising icons in the world, but Mr. Peanut once was just an idea in the head of a young Suffolk teen named Antonio Gentile.

Three of Gentile’s nephews are in town this weekend, coinciding with the Peanut Pals swap meet set for today from 9 a.m. to noon at the Suffolk Center for Cultural Arts. They plan to show off the original drawings of Mr. Peanut, which have stayed in the family, and give presentations to the Planters memorabilia collectors who have gathered in the city.

Gentile’s nephews say they are proud of their uncle’s involvement in creating the Planters icon, but he was much more than just the father of Mr. Peanut.

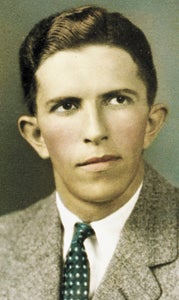

Gentile was one of eight children born to Italian immigrants who settled in Suffolk. His father was a tailor at West Brothers and his mother was a homemaker, nephew Peyton Lewis said. The couple built their own home on South Main Street and raised chickens in the backyard.

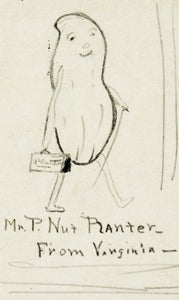

As the story goes, young Antonio responded to the contest put out by Planters Peanuts founder Amedeo Obici with a series of drawings of an anthropomorphized peanut with legs, arms and a face. The drawings depict Mr. Peanut doing a variety of activities — singing, somersaulting, riding a toy horse and, of course, serving peanuts.

Antonio received $5 for winning the contest, although nephew Bob Slade said he’s never been able to find any reference to the contest other than his uncle winning it.

“I’ve always suspected the selection of the drawing was not an objective process,” he said, noting the Obicis and Gentiles were among the few Italian families in Suffolk then.

The drawings were sent off to Pennsylvania, where Planters started, to a commercial artist who added a top hat and monocle — at least one of Gentile’s drawings already pictured Mr. Peanut with a cane. Slade’s efforts to figure out who the artist was have been unfruitful.

And so Mr. Peanut was born, with his print debut coming in the Feb. 23, 1918 edition of the Saturday Evening Post. But the relationship between the Obicis and Gentiles did not end there.

Obici paid not only Antonio’s way through college and medical school, but also paid for four of his siblings to attend college as well. Two did not survive to adulthood, and the last did not go to college.

“There’s no way in hell they could have done all that without outside assistance,” Slade said. “Even though they were socially disparate, the common bond was they were Italian.”

Obici even had his personal chauffeur drove some of the siblings to college on several occasions, Slade said, and the family often visited Obici’s farm.

After Antonio Gentile graduated as valedictorian of Jefferson High School and then from the University of Virginia, he became a physician at the Elizabeth Buxton Hospital in Newport News — named after the founder’s wife, as Obici named the hospital he funded after his wife Louise. Gentile married the former Delcy Ann Maney of Oklahoma.

About 11 months after his marriage, Gentile was at work when he died of a massive heart attack at the age of 36 in 1939. He is buried in Cedar Hill Cemetery beside his wife, on whose other side is her second husband.

As it turns out, Gentile applied the generosity learned from Obici to his own life. When his widow filed a statement of his estate, she listed about $12,500 in assets, but there was a footnote about $1,130 in debts he had co-signed on for patients that were not likely to be paid.

“He was not one who was in it for the compensation,” Slade said. “He was in it for the people he served.”

Gentile also lived a full life apart from work. He traveled to Italy in 1927, where he met Pope Pius XI. He corresponded with Franklin D. Roosevelt when the future president was assistant secretary of the Navy, and he wrote to and received a response from “Gone With the Wind” author Margaret Mitchell, on whose book he had taken copious notes.

Because he died so young, all the relatives who remember him personally are gone now. However, the three nephews remember their uncle by collecting memorabilia, but mostly only that related to their uncle.

“I tend to gravitate to the older print ads because of the relationship to the drawing itself,” Slade said.

Lewis said he wants his uncle to be remembered, but not just for creating Mr. Peanut.

“I want people to know he was more than just that,” he said.